上午好各位. 如果你们想去阅读文段在英文里,我转邮一个演讲文稿为满足各位. 同时一个事需要说明,我已经发送一个邮件给 BoE 并且获得相应的允许在提前里. 请阅读它认真的和开心的并且你将懂得什么我们的货币政策制定者是在面对和她/他们的智慧和幽默的感觉,我相信.

"

Speech by

RACHEL LOMAX

DEPUTY GOVERNOR OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND

UK MONETARY POLICY: THE INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT

At the APCIMS Annual Conference

On Monday 17 October 2005

Those of you who have logged on to the Bank of England’s website recently will have

noticed that it has turned a cheerful shade of orange. It is a lovely website and we are

very proud of it. But perhaps now was not the best time to major on pictures of happy

shoppers clutching bulging carrier bags! The fact is that website design - like

monetary policy - is beset by information problems and lengthy lags. These make it

very hard to get the timing of changes just right.

When the organisers of this conference pressed me for a title some weeks ago, I

decided to talk about the international context for UK monetary policy for two

reasons. First, I was fresh from a summer spent reading this year’s top business books,

whose key theme is the dizzying pace of change in the global economy. But second, I

wanted look beyond the shopping story that – understandably – tends to dominate the

press, to some of the other factors that have to be weighed when the MPC sets interest

rates.

But let me start with the recent weakness in retail spending. Judging by the latest

indicators, this looks like persisting, at least in the near term. But while spending on

retail goods has been virtually flat since last autumn, total consumer spending,

including services and utilities, has continued to grow, though quite slowly. And

while the prospects for consumption are clearly important, so too are those for other

key drivers of the economy, such as business investment and net exports. The

question is: if consumers decide to save more, are the conditions in place for other

sources of demand to take up the slack? The answer depends in part on what is

happening in the rest of the world.

Plainly, developments in the rest of the world will influence domestic monetary

policy. The UK is a very open economy, exposed to trends and shocks that affect

supply as well as demand, and our financial markets are fully integrated with global

markets. Sterling is one of the world’s most liquid currencies, and the FTSE 100 is

heavily weighted with multinational companies.

Let me give one example of what this can mean in practice. Over recent years, the

progressive shift toward sourcing from low cost producers has been depressing import

prices, and improving the terms on which we trade. This has exposed domestic

producers to intense competitive pressures, but it has been unambiguously good news

for consumers. And it has probably meant that the MPC has been able to set

somewhat lower interest rates to meet its inflation target.

The establishment of global markets in key asset classes has created complex linkages

between economies as well as facilitating better risk sharing. On the one hand, the

transmission of shocks has been speeded up – a generation ago, for example, who

would have supposed that devaluation in Thailand would have set off a chain reaction

that rippled through financial markets from New York to Tokyo?

On the other hand, the absorptive capacity of financial markets has massively

increased. This has helped to cushion the impact of major shocks on the wider

economy. But it has also facilitated the financing of huge current account imbalances.

These have been the number one issue on the IMF’s worry list for the past few years

and now constitute a significant source of risk to the world economic outlook.

So you might expect the MPC’s policy rate to respond to changes in the world

economic outlook, though you might speculate that the relationship could be quite

complex. What does recent experience show?

Between 2000 and 2004, there was, on the face of it, a very close relationship between

fluctuations in world GDP and the policy rate; as all main regions of the world slowed

after the stock market crash and the ending of the IT boom, the MPC first cut its

policy rate sharply – and then held it down until the world economy had clearly turned

the corner in the second half of 2003.

But it would be quite wrong to infer that the MPC ignored domestic demand during

this period – though the data have now been so heavily revised it is difficult to

generalise about past decisions. The important point is that the MPC’s approach then,

as now, is to form an overall judgement about demand relative to supply and, as far as

it can, to set the policy rate to keep the two in balance, so that inflationary pressure is

broadly constant. So with external demand very weak – and recall that by the end of

2001 world imports were actually falling – the logic of that approach pointed to

easing policy to encourage a faster growth in domestic demand.

This approach worked well in the sense that it helped to ensure that the UK went on

growing steadily through the world slowdown, while consumer price inflation

remained close to the Chancellor’s target. But there were side effects. One was a

marked increase in the UK’s trade deficit. Another was the creation of a monetary

climate conducive to strong rises in house prices and consumer borrowing relative to

disposable incomes – an experience shared with other countries such as Australia and

more recently the United States. Together with structural and demographic trends,

this has helped to push the ratio of both house prices and consumer borrowing to

household disposable incomes to levels well outside the range of previous experience.

If, against the background of a much flatter housing market, households now go

through a period of rather subdued spending, strong external demand would help to

support activity and rebalance the economy. But is that in prospect? And what are the

risks?

On some measures, last year – 2004 – saw the strongest growth in the world GDP in

30 years. While there has been some reduction in growth this year, most forecasters’

central expectation is that it will not prove very marked.

From a UK perspective however, the external conjuncture has been significantly less

supportive than this implies.

The key point is that the upturn in world growth has been very unbalanced, being

driven largely by the US and China. Measures of world activity which give a high

weight to these two countries paint a pretty buoyant picture, especially those which

use purchasing power parities. However, less than 2% of UK exports go to China and

rather less than 20% to the US. Fully 50% go to the euro area, which has grown only

sluggishly, and whose growth forecasts have persistently been revised down. And

Germany, Italy and the Netherlands – countries which between them take around 25%

of UK exports – have underperformed the euro average. As a result world GDP

weighted by countries’ importance in UK export markets has shown much a weaker

recovery.

World price pressures have also been stronger than in recent previous cycles. This

largely reflects the sharp rise in the price of oil since early 2004 – a development

which seems to have taken almost everyone by surprise. This is a complex story. On

the demand side, the relative importance of China and the US in powering the world

economy may help to explain why world oil demand grew quite so strongly relative to

world GDP last year. This year, however, the sharp rise in prices owes at least as

much to supply factors.

Allowing for these caveats, this is still a much stronger world economic background

than, say, 2001. But there are several important risks to this outlook.

The first concerns oil prices. So far the world economy has apparently taken a tripling

in oil prices in its stride, thanks to the much lower oil intensity of output, and the

greater flexibility in labour markets, in most advanced economies compared with a

generation ago. It is also true that the short term capacity of oil producing countries to

spend their increased revenues is now much greater than it was in the 70s. This helps

to explain why consensus forecasts for world GDP growth next year have remained

remarkably steady.

But there is a very high level of uncertainty about future oil prices. Judging by the oil

futures curve, the central view is that prices are likely to remain high, at around $60

per barrel for the next few years at least. This is in contrast to 2000, when the oil

futures curve was downward sloping. But the range of current Consensus forecasts is

very wide – from around $45 and $75 per barrel. And oil option prices – admittedly a

very imperfect measure – suggest that there is a 15% probability of oil prices rising

above $80 a barrel and a 5% probability of them falling below $40 in six months time.

If oil prices rise no further their impact on headline inflation should be temporary. But

a series of positive oil shocks might have the effect of pushing up headline inflation

for an uncomfortably long period. In contrast to the 1970s and 1980s, inflation

expectations in major oil consuming nations have been well anchored for the best part

of a decade. But there’s no room for complacency. The unfamiliar experience of

higher inflation might well dislodge those expectations, if there was any wavering in

central banks’ perceived commitment to keep inflation low. This could also prove

damaging to consumer and business confidence.

I claim no special insight into the oil market, and especially into its likely short term

movements. But it is hard to miss the longer term challenges which the rapid

economic development of China – and India – pose for resource markets, and

especially energy markets. China is now the world’s second largest oil importing

country after the US, and last year alone it accounted for nearly a third of the net

increase in world oil demand. In per capita terms, its own oil resources account for

less than 10% of the world average. Yet its oil demand is set to grow strongly in the

longer term. Oil supply is traditionally slow to respond to changing prices – lead times

for developing new fields are often around 3-7 years; and there are constraints on

refinery capacity which may influence petrol prices.

This is bound to have implications for the UK and for our European markets. Over the

past decade, we have benefited from the downward pressure on imported goods prices

exerted directly and indirectly by low cost production in Asia. Even if these trends

continue, as in principle they could for some time, it is becoming increasingly clear

that consumers may also need to contend with upward price pressures as world energy

markets adapt to meet the needs of emerging Asia.

The second key area of risk is global imbalances. These pose risks to foreign

exchange markets and to world activity. Higher oil prices have intensified the scale of

the problem. Yet we seem no closer to a denouement – indeed, as the US current

deficit topped 6% of GDP, the dollar has tended to strengthen. What does this mean

for the UK? I find it extremely hard to predict how sterling’s effective rate would be

affected, were there to be a major re rating of the dollar. But a resolution of global

imbalances which was accompanied by global recession would represent a major

challenge for us – one to which, I suspect, we are now less well placed to respond

than we were in 2001.

Finally, there is the puzzling matter of long term interest rates; last year, as central

banks raised their policy rates, long term nominal and real rates fell to levels not seen

in 40 years (though of course, US rates have now ticked up a bit recently). At the

same time, risk premia of all kinds – bond spreads and term premia – have been

sharply compressed.

This state of affairs has caused a great deal of head scratching, and nowhere more

than in central banks. Plausible explanations for low risk free real rates include the

possibility that there is a global savings glut. It is also argued that there has been an

investment ‘strike’ almost everywhere except China and maybe the US, perhaps

reflecting a persistent overhang from the East Asian crisis or the last IT cycle. These

are speculative explanations, and it is not easy to discriminate between them.

However, they all seem to point to a more or less prolonged period of low rates.

More worryingly, compressed risk premia of all kinds may reflect a belief that the

world is no longer such a risky place, a belief fostered by the period of low inflation

that many economies have enjoyed in the past decade. Hopefully, low inflation is here

to stay. But in some countries, notably the US and the UK, low inflation has been

coupled with an unusually low degree of output volatility; and this may have

encouraged an exaggerated notion of the role that central banks can play in achieving

exceptionally benign outcomes, in different circumstances.

Unrealistic expectations invite disappointment. And disappointment – if it dawns

suddenly – is liable to have a disruptive effect on financial markets and potentially on

real economies.

That is the dark side. But for now, low real interest rates are supporting activity, and

the main puzzle is why companies are not taking more advantage of favourable

financing conditions to increase their investment – though once they do, past

experience suggests that spending could rise could rise quite quickly.

Let me sum up. The immediate prospects for the world economy are still robust,

despite the sharp rise in oil prices. The outlook for UK weighted activity is less rosy,

with relatively subdued growth in the euro area – though even here the latest business

surveys are brighter than they have been for some time. The UK is fully exposed to

the impact of more adverse world pricing trends, notably higher oil prices. And there

are some significant risks, with considerable uncertainty about oil prices. This outlook

could provide some support for a rebalancing of the UK economy. But there is no

guarantee of that.

The MPC may face some hard choices in the coming months. Looking back on my

summer reading for inspiration – that list of the year’s top business books – I am

reminded of the mission statements of two of the companies under scrutiny. One was

Disney – whose aim is, famously, to ‘Make People Happy’. The other was Google –

whose mission statement urges, somewhat austerely, ‘Don’t be Evil’.

One thing is for sure: the MPC must not set out to rival Disney. So let Google be our

guide, as we search for a way through the policy maze. "

(ENDS) |

2025.12.16 图文交易计划:布油开放下行 关2383 人气#黄金外汇论坛

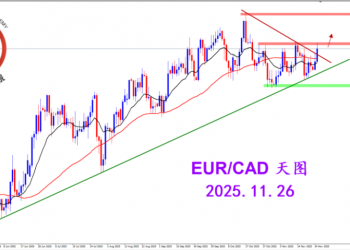

2025.12.16 图文交易计划:布油开放下行 关2383 人气#黄金外汇论坛 2025.11.26 图文交易计划:欧加试探拉升 关3116 人气#黄金外汇论坛

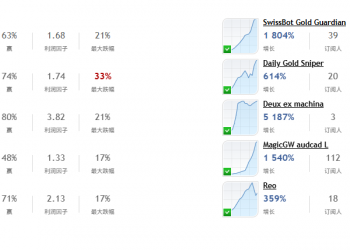

2025.11.26 图文交易计划:欧加试探拉升 关3116 人气#黄金外汇论坛 MQL5全球十大量化排行榜3162 人气#黄金外汇论坛

MQL5全球十大量化排行榜3162 人气#黄金外汇论坛 【认知】5970 人气#黄金外汇论坛

【认知】5970 人气#黄金外汇论坛